In 1935, American radio commentator Walter Winchell coined the term “Disc Jockey.” It would later be shortened to the more commonly used acronym, “DJ,” and for the next 50 years “DJs” practicing the art and science of playing records did so with vinyl records and turntables. During that time period, it was not easy being a DJ.

Equipment was expensive, the tricks of the trade were closely guarded secrets, and a substantial vinyl-record collection was a prerequisite to getting your foot in the door. Needless to say, the competition pool was small.

In 1999, when I began DJing as a college student, I knew few DJs, and even fewer who were willing to teach me. I managed to talk my way into an apprenticeship at an underground-dance-music FM-radio show and pestered the resident DJs to show me the ropes.

A substantial vinyl-record collection was a prerequisite to getting your foot in the door.

“OK, here’s how to slip-cue, there’s the headphone cue, and that’s the pitch control… good luck, kid.”

My first and only lesson went something like that. But, it was enough. I caught the bug, began collecting vinyl, and played out wherever I could get booked. For years, I lugged vinyl and did my best to absorb something from every DJ I met.

Read More: How to read and rotate your dancefloor

I eventually moved to New York City and made the switch to Serato Scratch Live in 2005. I was skeptical at first, but quickly became a supporter. Aside from the obvious physical advantages of using digital media, it was DJing as usual to me, albeit with a few more tricks.

Initially, club-goers were confused at seeing a laptop in the “disc-jockey booth.” Doesn’t he need to change the records? For the first few years, I was constantly educating my followers on the technology and assured them that my “DJ-ness” was still intact. But Serato was merely the tip of the iceberg. As we all know, newer technologies have replaced the need for vinyl discs and turntables altogether.

Of course, over time—in and out of the DJ culture—the questions about the notion of authenticity came flying. Are the seasoned DJs who have embraced these new technologies still DJs? What about the wannabes just getting their start? Are they “real DJs”? How and why has new technology changed the notion of the DJ?

You are a real DJ if you…

1. Relentlessly seek out new sounds

2. Are bent on building your music library

3. Strive to create interesting sonic juxtapositions

4. Enjoy causing epileptic fits of dancing

5. Hear three songs ahead of each one you play

6. A good beat makes the hair on the back of your neck stand on end

7. Are the one your friends call when they want to know where they should go to hear new music

8. Scope out the DJ booth at every venue you visit

9. Wouldn’t be caught dead without a pair of headphones on you

10. Have blown off a date or three for a gig

CDs, CDJs & Flash Drives: While compact discs had been around since 1982, it wasn’t until the creation of pitch-adjustable CD players in the mid-’90s, better known as CDJs, that DJs considered CDs a genuine vinyl alternative. Just under 5-inches wide, a single compact disc can hold 80 minutes of music – more than twice that of a 12-inch vinyl plate running at 33 RPM.

This saved the backs of many a DJ who had become accustomed to lugging heavy, vinyl-filled gig bags. In addition, the use of a laser in lieu of a needle for playback solved the latency problem that a motor-driven turntable created. Since the technology still requires a circular storage disc that spins, the disc jockey’s identity remained intact. CDJs were initially deemed gimmicky by club owners, but they have since become the default DJ setup at most major clubs around the globe, thanks to forward-thinking companies like Pioneer DJ. As a result, the move to CDJs now equipped with USB flash-drive readers have not caused nearly as much controversy as some of the following developments.

Digital Audio Workstations: In 2001, the Berlin-based music software company, Ableton AG, introduced an affordable digital audio workstation (DAW) with live remixing and performance in mind. An entire musical oeuvre can be created, manipulated, performed, and stored on a laptop. No turntables, CDJs, or discs of any kind are necessary, yet a “DJ” can cue songs, match beats, and add effects ad infinitum. Numerous DJ softwares—at a fraction of the cost, but without the production capabilities—quickly followed. The complete replacement of the classic DJ setup with a portable computer is regarded by many as sacrilege, but the best of both worlds for others.

Digital Vinyl System (DVS): In a marriage of old-meets-new-technology, the creation of vinyl-emulation software (and its initial release to the public in 2001) allowed for digital audio files stored on a laptop to be controlled through a time-coded piece of vinyl on a turntable via an external sound card. Think DeLorean hover conversion.

This allowed those uninterested or unwilling to give up the look and feel of vinyl something deemed essential to maintaining the art they had pioneered, the benefits of high-storage capacity, live looping, and audio effects.

DJ Controllers: The creation of the DJ controller was technology following its natural path of making things faster, more efficient, and compact. These devices began as the fusion of two turntables (or CDJs) and a mixer into a single portable rig. While there are no discs, there is an homage to traditional DJing via rotary controls and sliding faders.

A laptop computer, touchpad or even a smartphone can be used to run the software interface. The latest generation of controllers eschews the turntable reference altogether and focuses on triggering clips and effects with the simple push of an LED illuminated button. Moldover’s “Controllerism” is here to stay.

Touch-Screen Apps: The latest wave in DJ equipment is the development of powerful software applications for tablet computers, most notably the iPad, which was first released in 2010. Digital audio files are cued and manipulated via virtual faders and knobs with nothing more than the tip of one’s finger.

The advancement has already led to the development of Blade Runner-esque MIDI controllers like Smithson-Martin’s Emulator Elite.

The Debate: Today, there is an ongoing debate as to whether or not the users of these aforementioned technologies, most of whom have never even touched a classic DJ setup, are entitled to call themselves “real DJs” in the first place.

In one camp are the purists. These DJs adhere to the most literal interpretation of the term “disc jockey.” The “disc” refers to vinyl disc records and “jockey” refers to a machine operator. The turntable is the original playback machine. Purists do not consider anyone not utilizing records and turntables to be a “DJ.”

At the opposite end of the spectrum are the progressives. They believe that regardless of the technology used, or the medium preferred, the “DJ” is an umbrella term for anyone who plays pre-recorded music. The current Wikipedia entry for the definition of a “disc jockey” supports this claim stating, “A disc jockey (abbreviated D.J., DJ or deejay) is a person who plays recorded music for an audience, either a radio audience if the mix is broadcast or the audience in a venue such as a bar or nightclub… Today, the term includes all forms of music playback, no matter which medium is used.”

Purists do not consider anyone not utilizing records and turntables to be a “DJ.”

The physical manipulation of vinyl records for the sake of beat matching and turntable trickery, a significant focus of DJ culture, is often the criteria by which we measure whether someone is a “real DJ,” when, in fact, they did not exist at the time Mr. Winchell coined the term.

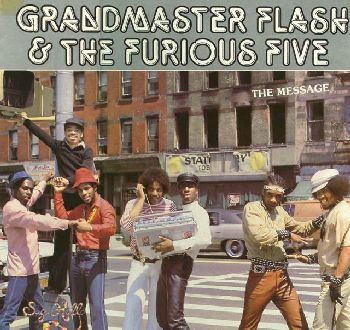

Believe it or not, Grandmaster Flash, the godfather of “turntablism,” was chastised for stopping a spinning record by placing his hand on the platter, something essential to cueing, during the development of his “quick-mix theory” in the ’70s. He, too, was not initially considered a “DJ” by some. But I dare you to walk into any DJ school now and utter the words, “Grandmaster Flash is not a true DJ.”

Clearly, the origin of the term was born of those individuals using the technology of the day. But why would an advance in said technology create such an uproar?

Grandmaster Flash, the godfather of “turntablism,” was chastised for stopping a spinning record by placing his hand on the platter, something essential to cueing.

The short answer is skill. Joel Davis, co-founder of All City Sound, a NYC-based audio/video rental, repair and installation company, says that for those looking to enter the world of DJing, the available technology includes “literally hundreds of options, separated by extreme minutia of details ranging from construction quality to component features and aesthetic appeal.”

Access to these newer technologies, which now automate numerous aspects of what DJs previously did manually, has upended the standards by which we measure a DJ’s ability. Advancements like quantization, beat-synching, looping, built-in effects, track previewing, and rapid loading make the most basic of turntable skills a relative cakewalk.

Numerous “jocks” out there rely on the latest advancements to meet the standards by which turntable DJs are measured, rather than raising the bar. Lazy laptop syndrome is bad for the progressive DJs out there with real skill who will be overlooked by purists simply because they are using newer technologies. Kid Capri, a judge for Smirnoff’s reality-TV DJ competition “Master of The Mix,” asserted his own puritanical position on KMBZ 98.1FM’s website. “I’m not fully down with all of the technology that’s coming out and taking away the essence of what it is,” he said. “The essence of what a deejay is… is two turntables, a mixer and a mic.”

It’s no wonder that the lonely iPad DJ on the show, DJ Hohme, was booted just two episodes into Season 3. DJ Premier goes even further in D.J.P’s documentary, For Promotional Use Only, claiming, “You need to own at least 1,000 records to call yourself a DJ.”

Lazy laptop syndrome is bad for the progressive DJs out there with real skill who will be overlooked by purists simply because they are using newer technologies.

An unexpected side effect of the purist’s stance is that someone can cash in on the cultural currency of the “DJ” moniker by simply using an older technology. These days, a pair of turntables is as much a vintage fashion statement as a Sailor Jerry tattoo.

One mechanism progressive DJs use to earn the respect of older DJs is by learning the art of DJing by starting with turntables before moving on to the newer technologies. In The Scratch DJ Academy Guide: On The Record, British turntablist DJ Yoda says, “I think it’s important to get used to working with vinyl first. It’s crucial to have that basis, because the new technology just emulates two turntables and a mixer. Then, when you’ve mastered turntables, you can take advantage of the new toys.”

The thinking here is that it instills an appreciation for the art form that has been painstakingly built over many years, and gives aspiring DJs a point of reference for advancing the art with newer technologies in ways that were previously not possible.

Progress & Change: History shows that that the current state of DJing would not have been possible without the techniques and innovations of the early pioneers, but the purists must realize that their skills have not been usurped. They were essential to the evolution of this postmodern art form, and are inseparable from the identity of the DJ. The meaning of what it is to be a DJ has expanded, and it will continue to do so, regardless of whether or not those who took part in a particular stage of its development recognize it.

The Nobel Prize-winning playwright George Bernard Shaw once said, “Progress is impossible without change, and those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything.” DJs once changed their mind about Grandmaster Flash and it would be hypocritical to consider him an exception to the rule.

The meaning of what it is to be a DJ has expanded, and it will continue to do so, regardless of whether or not those who took part in a particular stage of its development recognize it.

Truth be told, records and turntables were merely the first available technologies that enabled someone to manipulate pre-recorded sounds in a live performance and make connections between all types of music in a way that would otherwise be a daunting, if not an impossible, task.

Since the established cultural cache of being called a “DJ” is preferred to that of say, a “Playback Jockey,” despite the fact that most of us started our musical journey in our bedrooms playing music in our sweatpants, the power of the “DJ” tag has been diluted by the overwhelming number of people claiming the moniker. But not every person wielding two turntables and a mixer are “DJs” any more than people gluing feathers to their backsides are chickens.

The coveted DJ title should be reserved for those that put in the time and effort to deliver a superior musical experience to those around them. In a recent interview, DJ/producer Kevin McHugh (aka Ambivalent) responded to the question of whether a DJ is defined by the equipment he uses. “The only people who should know which gear is used in the booth are the DJ and the club’s sound technician,” he said. “I guarantee that the most important information about a DJ set can be ascertained with your eyes closed and your body moving.”

The coveted DJ title should be reserved for those that put in the time and effort to deliver a superior musical experience to those around them.

Wise words. Technology has changed over the years, but the intentions of real DJs are the same. If you are someone who relentlessly seeks out new sounds, are bent on building your music library, strive to create interesting sonic juxtapositions, enjoy causing epileptic fits of dancing, hear three songs ahead of each one you play, a good beat makes the hair on the back of your neck stand on end, are the one your friends call when they want to know where they should go to hear new music, you scope out the DJ booth at every venue you visit, wouldn’t be caught dead without a pair of headphones on you, and have blown off a date or three for a gig, then you are a “real DJ.”

Chris Alker is a New York-based DJ, architect, and writer. He is one-half of the DJ duo, DELUXE.